John, get out!

The unforgettable life of Swiss test pilot Hans Bardill

In July 2021, Airbus towed a restored airliner onto a meadow near the assembly halls of its Hamburg facility, where some aircraft were already on display that played significant roles in the European aerospace group’s history and the company’s German operation in particular.

For the 50th anniversary of the VFW 614’s first flight – the first German jet airliner developed and built in serial production – apprentices at Airbus’ plant on the former island of Finkenwerder had spruced up one of the few remaining examples of the unusual short-haul jet and freshly repainted it in its former livery.

One small detail differed from the original VFW factory colours, however, which had a great effect on former employees and those familiar with the aircraft built in the nearby city of Bremen: next to the entrance door was the name of Swiss test pilot Hans Bardill.

He was in the cockpit during the VFW 614’s first flight on 14 July 1971, but died half a year later at the age of 39 when the prototype crashed during a test flight on 1 February 1972.

Hans Bardill was an extraordinary man. He was not only an excellent pilot and engineer, but above all had a great personality who left a deep impression on colleagues and friends and is fondly remembered to this day. Furthermore, he was a dearly loved husband and father to his young family.

AT HOME IN SCHIERS

Bardill was born on 19 June 1932 in Schiers in the canton of Graubünden as the eldest of 10 siblings. His father worked as a teacher and was engaged in various communal roles in the Prättigau region.

Bardill was enthusiastic about aviation from an early age and had his first flying experiences in gliders at the age of 16. After graduating from high school, he trained as a pilot in the Swiss Air Force and flew, among other aircraft, Pilatus P-2 trainers, Morane-Saulnier D-3800 propeller fighters and De Havilland DH.100 Vampire Jets.

Air force flying was not enough for him, however, and so he studied mechanical engineering at the university of science and technology ETH in Zürich during his military service. Later, Bardill considered working at the Alpine nation’s then-flag carrier Swissair, but the routine airline operations with fixed flight schedules and procedures did not appeal to him.

Bardill became a test pilot at the Flug- und Fahrzeugwerke in Altenrhein and flew the P-16 ground attack aircraft, which was under development there for the Swiss Air Force. The single-engine jet had taken off for its first flight in 1955, but never entered serial production because the government in Berne withdrew its support for the project in 1958 after two test aircraft had crashed. Only one of five P-16s built has survived and is now on display at the Flieger-Flab-Museum in Dübendorf near Zürich.

P-16 programme leader Dr. Hans Studer tried to rescue his team’s effort by collaborating with US inventor and entrepreneur William Lear to develop a business jet based on the P-16’s design. Lear had previously converted propeller aircraft for business customers and saw a market for a purpose-built small jet for customers with a lot of money and little time.

The co-operation with the Swiss development team, which included Bardill, led to the first LearJet – the epitome of a light business jet. The wings of the P-16 with their characteristic tip tanks were thus adopted for the new aircraft. But contrary to original ideas of binational assembly lines, production of the LearJet began in the US alone under Lear’s leadership

OFF TO HAMBURG

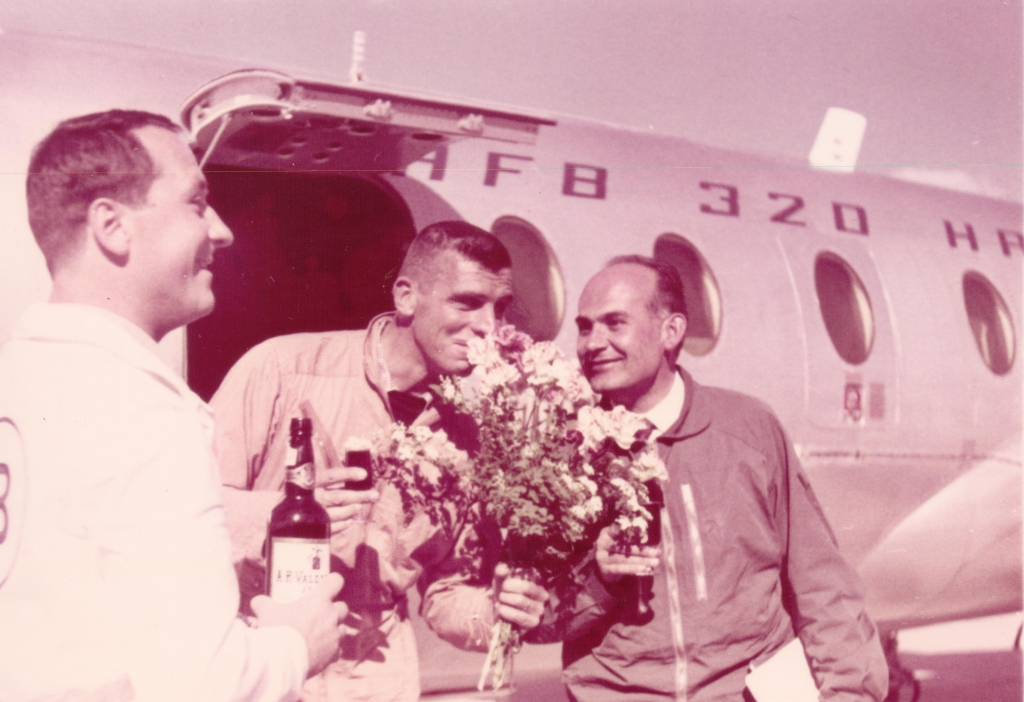

Soon thereafter, Studer took over the programme management for the HFB 320 Hansa business jet at Hamburger Flugzeugbau – a predecessor company of today’s Airbus plant in the German city – and Bardill followed him there. Ironically, the LearJet became a main competitor for the HFB 320, which was designed for seven passengers but could accommodate up to 12 travellers in a commuter cabin configuration.

Bardill moved to Hamburg with his family in 1963. Two years earlier he had married his childhood sweetheart Elsbeth Tarnutzer, who had grown up on a mountain farm above Schiers and became a kindergarten teacher. The two had known each other since school age and became closer friends as teenagers. After he picked her up from the train in Zürich at 4:00am – unexpectedly for Elsbeth – on arrival from Paris where she had spent some time as an au pair, they became a couple.

Their first daughter was born in 1961, and the second arrived in Hamburg in 1964. A terraced house on the city’s southern outskirts – close to heather land in Fischbek and the fruit-growing areas in the Alte Land – became the young family’s home.

During the HFB 320’s first flight on 21 April 1964, Bardill sat in the cockpit as co-pilot and flight test engineer next to HFB chief test pilot Loren William Davis.

The 38-year-old US American – nicknamed “Swede” because of his Swedish mother and towering height – had previously completed test and certification campaigns for various engine programmes at HFB 320 engine supplier General Electric, and therefore brought valuable experience to the German development team.

A key feature of the curious German Hansa Jet was forward swept wings, which had its origins in the development of Junkers’ Ju-287 bomber during the 1940s. The unusual wing shape was selected for the HFB 320 partly because it enabled the central wing construction to be installed in the rear fuselage, aft of the cabin, and thus achieve standing height inside the passenger area.

Soon after the first flight, the flight test programme moved to Torrejón air base near Madrid. Spanish aircraft manufacturer CASA produced the rear fuselage and empennage for the HFB 320; friendly ties existed between the two companies; and Spain provided better weather and more open airspace than Germany for flight testing.

A year after the first flight, on 21 April 1965, the test team celebrated the 100th flight of the HFB 320 prototype V1. But three weeks later, on 12 May 1965, the silvery polished aircraft registered D-CHFB crashed near the city of Cuenca, about halfway between Madrid and Valencia.

Davis and Bardill had been exploring the HFB 320’s stall behaviour. During that manoeuvre, the aircraft’s angle of attack is increased by progressively raising the nose until the air flow around the wings starts to become turbulent instead of flowing around the aerofoils in an orderly manner. At that angle of attack, lift is lost and the aircraft begins to descend.

Every aircraft’s behaviour must be assessed in these conditions, and every pilot must be trained to recover from that situation. Lowering the aircraft nose usually decreases the angle of attack, which enables the wings to generate lift again and the pilot to regain control.

The HFB 320, however, had a treacherous weakness that was largely unknown at the time. The horizontal stabilizer, which is used to control pitch, is mounted on top of the fin. On aircraft with such T-tails and rear-mounted engines, the horizontal stabiliser can be inside an area of turbulence coming from the wings and fuselage at high angles of attack.

With no clean airflow around the horizontal stabiliser, the control surfaces lose effectiveness and the pilot can no longer steer the aircraft out of that situation. This condition is known as a super or deep stall – the aircraft is locked in.

Davis and Bardill found themselves in that condition at an altitude of about 22,000 feet (6,700m). After the stall, the aircraft secondarily went into a flat spin. It turned around its vertical axis at low forward speed – similar to a sycamore seed – while descending toward the ground without control. The two pilots attempted to create a nose-down momentum by deploying an anti-spin chute from the aircraft’s tail. But the chute did not have the desired effect of returning the aircraft to controlled flight.

About 30 seconds after the initial stall, Davis instructed Bardill: “John, get out!” Bardill then tried to open the aircraft door. About 1 minute 20 seconds into the stall, Davis reported to the tower in Torrejón, “I think we are going to get killed in that thing.”

Less than a minute before impact on the ground, Bardill was able to open the exit and jump out of the aircraft. Davis followed him, but he became entangled in the anti-spin chute. It is assumed that he tried to free himself because a knife that Davis usually carried in his flight suit’s knee pocket was not there later on. He did not succeed.

The aircraft hit the ground at a vertical speed in excess of 42m per second (8,280 ft/min) and came to rest on a slope outside the town of La Parra de Las Vegas. Bardill escaped the accident with his life.

The HFB 320 was not the only T-tail aircraft with deep-stall characteristics, which crashed during test flights. In 1963, British Aircraft Corporation had lost the prototype of its BAC 1-11 airliner in similar circumstances, and the two would not remain the only ones.

At the time, all manufacturers of T-tail aircraft were trying to get to the bottom of the deep-stall phenomenon, and they shared their experiences with each other.

Wolfgang Issel, who was part of the HFB 320 flight test team and witnessed the Cuenca crash from Torrejón tower, says that although manufacturers could observe the effects of deep stall on their aircraft at the time, none of them were able to explain what was happening because there were no aerodynamic studies and data available about the condition.

With modern wind tunnels and measuring techniques, the quality of aerodynamic data has enormously improved. Coupled with modern computing power, engineers today have access to computational fluid dynamics software that can realistically predict aircraft behaviour and enable engineers to change design parameters and simulate their effects.

During the 1960s, however, flight performance predictions for new aircraft designs were based on rudimentary measurements and experience from previous projects. The task of test pilots was to verify the designers’ predictions and find out if there were any surprises around the edges of the flight envelope.

After the accident in Spain, HFB conducted wind tunnel tests at a facility in Lille where a local engineer who had become highly experienced with flat-spin studies. His capabilities were so valuable that other manufacturers used the French facility for their studies too.

Issel notes: “The measuring technique for these tests was high-speed filming and evaluating changes in the flight trajectory on individual frames. We laugh about that today, but there was no other method at the time.”

The HFB 320 was granted type certification from the West-German civil aviation authority and US Federal Aviation Administration in 1967, as the first German aircraft with an anti-stall system. These systems warn pilots of an imminent stall through a stick-shaker and, if the pilot fails to intervene, by automatically pushing down the nose. Such systems were installed on other aircraft with similar characteristics as well.

After the type certification, Bardill took over management of HFB’s flight test department, which by then mainly assessed the functionality of newly built aircraft before delivery to customers. But Bardill did not find the office work associated with that job and reduced flying activity fulfilling.

On one hand, he missed flying. The author’s mother, Christel Gubisch – she had been part of the Madrid team and went on to become Bardill’s secretary at the flight test department – says that he occasionally hired one of the company’s light aircraft to go up for a spin. “I’ll just put on my flying dress,” she recalls Bardill as saying in such moments.

On the other hand, it quickly became clear that the HFB 320 was not going to become a commercial success. For Bardill, there was not much to do in Hamburg as a test pilot.

OFF TO BREMEN

About an hour’s drive away, in Bremen, development of the VFW 614 was meanwhile under way and flight tests there were being prepared. In 1970, Bardill joined then German-Dutch group VFW-Fokker as test pilot and engineer under the leadership of that company’s Danish chief test pilot Leif Nielsen.

Bardill and Nielsen were at the controls of the prototype D-BABA during its first flight from Bremen airport on 14 July 1971. The VFW 614 featured an unusual engine installation on pylons on top of the wings rather than underneath them. The 44-seater was developed for short-haul flights with limited demand. Passengers were meant to travel with the twinjet on regional routes with the same speed and comfort of larger airliners.

That concept became successful during the 1990s and led to high production volumes at Canadian manufacturer Bombardier and Embraer in Brazil. The VFW 614 did not enjoy such success during the 1970s, however. After initial service with regional airlines in Denmark and France, three VFW 614s became part of the German Air Force’s government transport wing until 1998.

The aircraft on display in Hamburg today was temporarily employed to test a digital fly-by-wire flight control system during the 1990s. The last flying VFW 614 operated at German aerospace research centre DLR as a test aircraft and was decommissioned in 2012. Out of 19 completed VFW 614s, six have survived.

The aircraft’s flutter behaviour was to be examined during a test flight in October 1971. For that purpose, small rockets were installed on the wings and stabilisers. These were ignited at different speeds and aircraft configurations in order to generate vibrations and determine the airframe structure’s capability of dampening them.

During these tests, the horizontal stabiliser began to flutter, which caused vibrations throughout the aircraft. Nielsen was able to arrest the flutter by reducing speed through thrust throttling and pulling the nose up. The aircraft landed safely in Bremen, but the horizontal stabiliser was structurally damaged during the flight and had to be replaced.

The prototype remained on the ground for repairs and installation of elevator flutter dampers until the end of January 1972. On 1 February, Nielsen and Bardill went up with the modified aircraft to confirm its flight characteristics. Flight test engineer Jürgen Hammer was on board too. The flight initially proceeded without unusual events. Critical manoeuvres were not being flown.

But after initiating a left turn at an altitude of around 10,000 feet near Bremen airport, the horizontal stabiliser fluttered again. This time, Nielsen was unable to stop the flutter and ordered the crew to abandon the aircraft.

The three men struggled to reach and open the emergency exit in the cabin floor behind the cockpit in the out-of-control aircraft. Hammer and Nielsen managed to get out and deploy their parachutes. Bardill managed to leave the aircraft too – as the last crew member – but he was severely injured while exiting the aircraft and was unable to deploy his parachute.

He was later found near the crash site. The aircraft had fallen almost vertically onto a meadow next to Bremen airport’s runway and disappeared into a deep crater.

Hans Bardill was buried in Schiers with large attendance from his home community. His widow Elsbeth subsequently built a house in the village, but she preferred to stay in the terraced house in Hamburg, which she had shared with Hans, for a further 45 years.

It was not until she was 85 that Elsbeth moved to Düsseldorf, to be closer to her first daughter and her family. There she celebrated her 90th birthday at the end of December 2021. Her second daughter went back to Switzerland after her studies and early career in Germany and now lives with her family in Zürich.

As a result of the accident, the VFW 614’s elevator control system was modified. The horizontal stabiliser flutter did not occur again.

If Bardill had survived the accident in Bremen , it can be assumed that – like after the crash in Spain – he would have wanted to continue flying and his job would have led him to Airbus. Civil aircraft production in Europe has largely consolidated around the Airbus programme since the 1970s.

Bardill’s colleague Jürgen Hammer subsequently joined Airbus and was among the first ranks of the airframer’s flight test crews during the 1980s and 90s. He served as flight test engineer on the first flights of the A320 and A340.

What set Bardill apart from others – beyond aviation – was his great personality and ability to engage with people. Several of his colleagues from the Madrid days belonged to a circle of friends of the author’s parents. Elsbeth Bardill is still a close friend of my mother’s.

Everyone who personally knew Hans Bardill always spoke of him in highest regard and made it clear what a remarkable and warm-hearted man he had been. A critical word was never mentioned about him in that circle.

“Hans was never a careerist focussed on climbing up the ladder,” Bardill’s HFB/VFW colleague and friend Wolfgang Issel says. “He was very modest and held himself back. That was the nice thing about him, he never put himself in the foreground and was just a team player.”

Bardill was happy to share his knowledge and experience with colleagues and was an “ideal boss”, says Issel. He compares Bardill’s attitude toward colleagues to that of a father with his children. “He was a very balanced person who, when there was a conflict… always tried to come to a sensible compromise.

“He was always very open, very straight forward, and always open to dialogue… He was just a great guy.”

“He could have been a vicar, everyone trusted him,” says my mother. She describes him as “full of life” because he was very sociable and enjoyed partying with friends and colleagues. Many photos in my parents’ album from their time in Madrid show Bardill talking, laughing, chinking glasses and dancing among his colleagues.

“He got along well with everyone and he never acted like he was anything special. He didn’t like that,” says Elsbeth. She sees the origin of Hans’ modest and unpretentious nature in what she describes as a “simple life” in Schiers.

“He was an enthusiastic pilot and certainly knew that he had a dangerous job. He said that to me as well,” Elsbeth says. She mentions that she was worried after the first accident in Spain. His reply at the time in their shared Swiss German was: “Ach, das goht schu” – oh, it’ll be fine.

“He wasn’t scared at all. Flying was just his thing,” Elsbeth says. With the awareness of the risks associated with his job, he nevertheless acted responsibly and always thought of his family first. “He made preparations that me and my girls would be well cared for if anything happened to him,” Elsbeth says.